Mirror interview

Optimal development

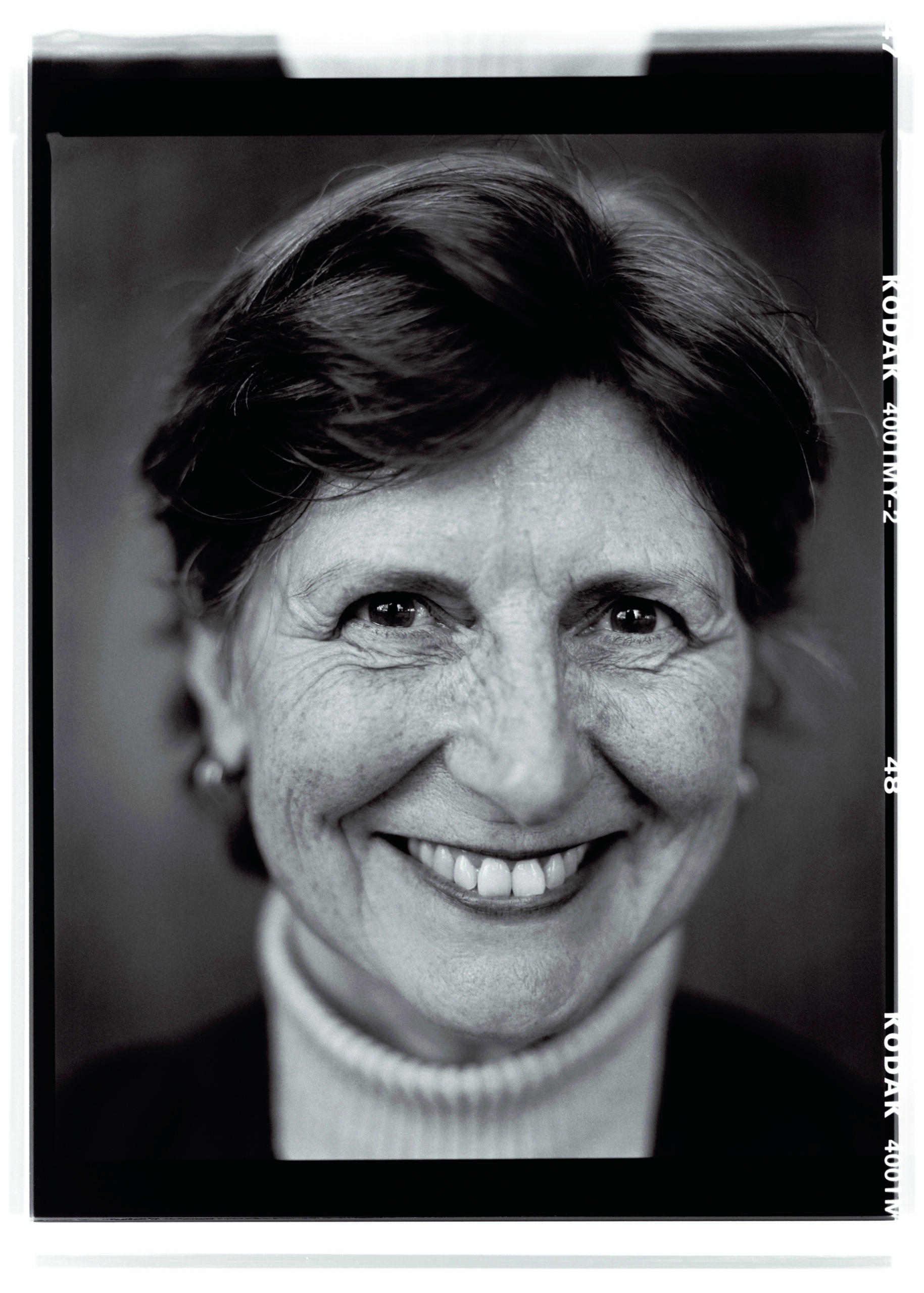

Developmental psychologist Eveline Crone discovered that the brain is sensitive to rewards. These include physical rewards for yourself, like winning money, but also social ones, like when you do something good for others.

Eveline Crone (1975) studies the adolescent brain. She states that the notoriously awkward stage of puberty is essential in a person’s development. She is head of the L-CID study in Leiden.

What does your research involve?

‘I study how young people can grow up in the best possible way; how their social worlds, such as parents, school, and friends, interact. My staff and I pay attention to a person’s environment and personal characteristics. We are particularly interested in how it is possible that people are sometimes focused on the well-being of others and at other times on their own well-being. How do you balance between these interests? We take into account all kinds of influences from the environment, such as the neighbourhood in which the child grows up, the role of the family, and that of friends. Together, these social worlds influence who the child is.’

How do you research that?

‘Using brain research, questionnaires, and, recently, youth and teacher panels. We deliberately combine different research methods; none is perfect. At the L-CID, we are following five hundred families with twins for several years. We are studying whether personal and positive parenting advice to parents has an effect on their children’s development. Using brain research, we then look, for example, at how the brain responds to rejection or reward. But the results in themselves do not say everything, so we put them alongside those of other methods. This gives us an overall picture.’

What are your main findings so far?

‘We found that adolescent brains respond strongly to rewards. This can lead, for example, to experimenting with alcohol and drugs. But it can also lead to social behaviour, because working together also releases a pleasant feeling in your brain.

An interesting new twist in our research is that you can categorise behavioural patterns into profiles, combinations of behavioural traits. For example, people who are empathetic on the one hand, but who are good at standing up for themselves on the other. By the way, there is not necessarily one optimal profile. All these people, falling under all these different profiles, are needed to form a good society.’

Ideally, what do you want to achieve?

‘I want to find out what young people need to discover their own talents and find their way in the complexity of today’s society. The aim is to make sure young people are not pigeonholed into a single category.’

What do you do when you are not working?

‘With me, private life and work are completely intertwined. I do not really have a good work-life balance, so to speak. I enjoy doing fun things with my husband and children. But I also like taking them to work events, and I enjoy working with nice people.’

Ideally, neuroscientist Hilleke Hulshoff Pol would like to give everyone a chance to develop to their full potential. She explores how the growth and shrinkage of our brains are related to this.

Hilleke Hulshoff Pol (1962) works in brain research. At the YOUth study in Utrecht, she uses MRI scans to study how brains change throughout life.

What does your research involve?

‘I study how brains grow and shrink throughout life. Our brains continue to evolve throughout our lives, constantly adapting to new environments and life stages. It is fascinating that we can now see in an individual how connections in the brain develop over time, and how these connections are affected by genes or experiences.’

How do you research that?

‘We ask children to come in for an MRI scan of their brain every three years. This approach with repeated measurements has since been applied in several locations around the world, but in the Netherlands, we were pioneers. We have already been able to collect the data of more than three thousand children in the YOUth study, even from babies before birth, in their mothers’ wombs.

Worldwide, we and other researchers have measured the brains of over 15,000 people of all ages twice, so that’s over 30,000 scans. It is fantastic what you can achieve when you work together. Among other things, we looked at brain development in childhood and adolescence.’

What are your main findings so far?

‘The biggest breakthrough of our research is that we have proved that genes affect brain growth or shrinkage. We also have evidence that these changes affect how we function, how we develop, how we age, and possibly the development of psychiatric disorders.’

Ideally, what do you want to achieve with your research?

‘What you would like is to give everyone the opportunity to develop to their full potential, taking into account their own unique combination of genes, environment, and experience. My research in itself cannot be directly applied to, for example, diagnosis of disorders; that requires a much broader approach. But it does contribute to discovering the mechanisms behind certain conditions.’

What do you do when you are not working?

‘I like to spend time with my husband and my two adult children. And I love walking the dog. And actually… actually, I would like to make time to sculpt, like I have done in the past. I am very visually inclined and find it fascinating to shape things threedimensionally.’

Eveline Crone was head of the L-CID study. She is professor at Leiden University. Hilleke Hulshoff Pol is professor at Utrecht University and UMC Utrecht.

This article is part of a New Scientist special issue about the Consortium on Individual Development, that will appear in September 2023.