News

The building blocks of social competence: an animal model approach

By Rixt van der Veen & Katerina Kalamari

Picture this: The main difference between your test subjects is an experience of neglect in early childhood, or harsh conditions or maybe a demanding adolescence. Their remaining life context is very similar -they might express a clear difference in certain genes, but this would be known to you- and when you invite your subjects to the lab to test their social competence, you are precisely aware of their previous activities, diet and life style….

The picture painted above would greatly help in pinpointing key experiences in important developmental periods and in unraveling underlying biological mechanisms, without having to account for the huge differences in life paths of each individual. And this is exactly why, in search for the building blocks of social competence, the CID consortium has also integrated rodents models (read more here). With these models we can study the main concepts of behavioural control and (pro) social behaviour in more tightly controlled settings compared to the human situation.

Which factors are examined by CID researchers in rodent models?

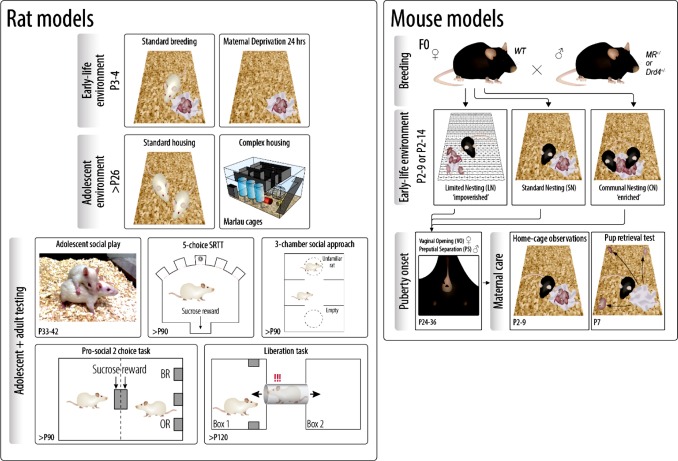

Using both rat and mouse models, depending on the read-outs of interest, we impose early life environments and test social competence in adolescence and adult life. Rats show an extensive social behaviour repertoire and display robust sociability towards members of their own group, while it is easier to exert control over genetic background and study gene-environment interactions in mice. In our mouse studies we work with mice differently expressing either the dopamine receptor gene (DRD4) or the cortisol mineralocorticoid receptor gene (MR), both implicated in sensitivity to environmental factors.

Mice models that can be more directly related to human research

In mice, we used maternal care behaviour as a read-out of social behaviour. We looked at care taking behaviour per se, like licking and grooming of the pups, but also at fragmentation and predictability of care taking behaviour. These latter can be more directly related to human research. During early postnatal life, we exposed mouse litters (dams with pups) to either impoverished or enriched conditions, consisting of access to very limited bedding and nesting material or ample material and communal nesting with two dams nesting together. We show that these early life conditions influence bodyweight and puberty onset of the developing pups and have an impact on the caring behaviour of these pups as adults, when they themselves raise their litter (PhD project Jelle Knop).

Rat models to test impact early life on social behaviour

To test the impact of early life conditions on more generalized (pro) social behaviour we exposed rat pups to challenging experiences in different developmental periods. In the early postnatal period, pups were deprived form their mother for a prolonged period of 24h. During adolescence -another sensitive period of development- animals were housed with many conspecifics in large ‘complex’ cages containing two floors, running wheels and mazes for cognitive stimulation. While bodyweight is influenced by maternal deprivation, and recognition of strangers is slightly affected, we find surprisingly little effects of this very early life experience on other social behaviours in either adolescence or adulthood. Complex housing starting in adolescence however, clearly affects social play in adolescence and social interest in strangers in adulthood. Moreover, complex housed animals show an increase in attention and diminished behavioural inhibition in the 5-choice serial reaction time task, a rodent version of the continuous performance task in humans.

Examining pro-social helping behaviour

There are not many existing rodent tasks that test the concept of pro-social helping behaviour, a behaviour extensively tested in the human cohorts. We therefore have adapted two tasks that measure pro-sociality, one task where we can measure the motivation to liberate a trapped conspecific and a task where a rat can choose to provide a sugar reward for either itself of for both itself and a partner rat. In this special issue paper we describe the set-up of this latter sugar task. Two PhDs in our lab, Jiska Kentrop and Katerina Kalamari were involved in these experiments and they compared the pro-sociality of animals that are either housed under standard lab conditions, or in the much more challenging ‘complex’ cages. Who is more willing to share?

Video: Katerina Kalamari explains the pro-social two-choice task in rats.

Overall, interknitted designs of human and animal studies have the advantage of building bridges between different disciplines. The CID consortium is a nice example of such a bridge and will hopefully inspire much more interdisciplinary research.

More information

Rixt van der Veen, Valeria Bonapersona, Marian Joëls (2020) The relevance of a rodent cohort in the Consortium on Individual Development. Developmental cognitive neuroscience DOI: 10.1016/j.dcn.2020.100846

Jiska Kentrop, Aikaterini Kalamari, Chiara Hinna Danesi, John J.Kentrop, Marinus H. van IJzendoorn, Marian J. Bakermans-Kranenburg, Marian Joëls, Rixt van der Veen (2020) Pro-social preference in an automated operant two-choice reward task under different housing conditions: Exploratory studies on pro-social decision making. Developmental cognitive neuroscience DOI: 10.1016/j.dcn.2020.100827

These papers are part of a special issue in Developmental cognitive neuroscience about the Consortium on Individual Development. For an overview of all papers go to here.